My earliest memories are of the round dining-room table in our Italian countryside home, its surface buried beneath onion-skin overlays of the Giza Plateau I found in a drawer. In the ’70s my father and his elder brother—both industrial designers in their thirties—had been commissioned to produce the master cut-away drawings for a prestigious European encyclopedia. Night after night I fell asleep imagining the dry hiss of Rotring pens and the smell of india-ink while they argued over the exact angle of the Great Pyramid’s descending passage. Those blueprints—got archived when the volume went to press.

By the time I was twelve my father had begun sharing the scraps of oral lore that had drifted in with the assignment: rumours of shafts far deeper than Petrie’s plumb-lines, talk of a geometric “signal pattern” that only made sense when plotted from far above Earth, hints that the casing blocks were older than the limestone core. Most academic visitors dismissed such claims as romantic noise, but my father retained the conviction that the pyramids pre-dated dynastic Egypt by tens of millennia—an intuition he could never prove, yet never abandoned.

Thirty years later, on a humid May evening in 2016, I carried those half-formed family legends through the heavy oak doors of the Explorers Club townhouse at 46 East 70th Street. The flag that had ridden Apollo 11 whipped overhead; inside, oil portraits and polar-bear taxidermy lined wood-panelled halls whose air smelled of beeswax, Scotch and old vellum. Past the trophy room a spiral stair led me to the library, where 13 000 expedition volumes rose in galleries around a Persian rug and a crackling hearth whose mantel was flanked—controversially—by elephant tusks. There, beneath the watchful glass eyes of Percy the polar bear and in the glow of shaded bank-lamps, sat the evening’s quiet centre of gravity: Dr A., an emeritus planetary geologist whose career had threaded NASA mapping projects and Cold-War seismology.

Dr A. waited until the doors were shut, then unrolled a sleeve of sepia seismograms recorded during classified deep-penetration tests in 1959. Faint hyperbolic traces on the printouts, he explained, betrayed cylindrical voids—eight of them—aligned beneath the plateau and plunging well beyond the 100-metre reach of any known Old-Kingdom work. He cross-laid orbital-mechanics plots showing that the three main pyramids form an isosceles triangle whose node angles resolve into near-integer multiples of arc-seconds when observed from a 600-kilometre polar orbit, turning the plateau into a kind of planar fiducial visible to any incoming spacecraft. The structure, he argued, could only have served visitors who required a stable optical marker and a protected depository deep enough to ride out climatic cataclysms. His working date—derived from precessional star-fits—was not 2600 BCE but something older than 20 000 BCE, when the north-pole orientation matched the shafts’ current azimuths.

Dr. A drew us close to the reading-table’s green-shaded lamps and—his fingers trembling on a chipped porcelain teacup—unspooled the core of his thesis: that at the twilight of the last ice age an expeditionary culture of breathtaking technological sophistication touched down on the Giza plateau, cored twin-spiral shafts deep into the limestone, and sealed within them “time-capsule rooms” packed with data-crystals, star charts and seed vaults meant to jump-start civilization after planetary catastrophes. The three giant pyramids, he insisted, were engineered not as tombs but as colossal triangulation markers whose geometry, albedo and spectral reflectance advertise Earth’s safe-harbour coordinates to any future wayfarers sweeping the planet from high orbit; in essence, luminous runway lights for the cosmos, left by one visiting human intelligence to guide the next.

Dr A argued that tectonically stable Giza was chosen to outlast any cataclysm, the pyramids engineered not as shrines but as indestructible backup nodes—safekeeping humanity’s data until the next wave of visitors, long before later cultures draped them in spirituality.

I felt the room tilt; here was a synthesis of my father’s hunches, delivered with the rigour of a man who had spent forty years measuring lunar mascons. Yet even Dr A. admitted that his dossier would die an anecdote unless someone found an imaging technology equal to the limestone’s attenuating grip. He closed his presentation with a prediction: “Before ten years are out, radar interferometry will show those shafts in the round.” Sadly, he passed away a few years later, and that serendipitous evening remained the only time our paths ever crossed.

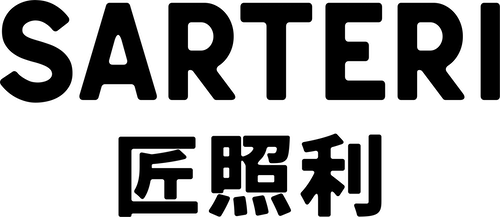

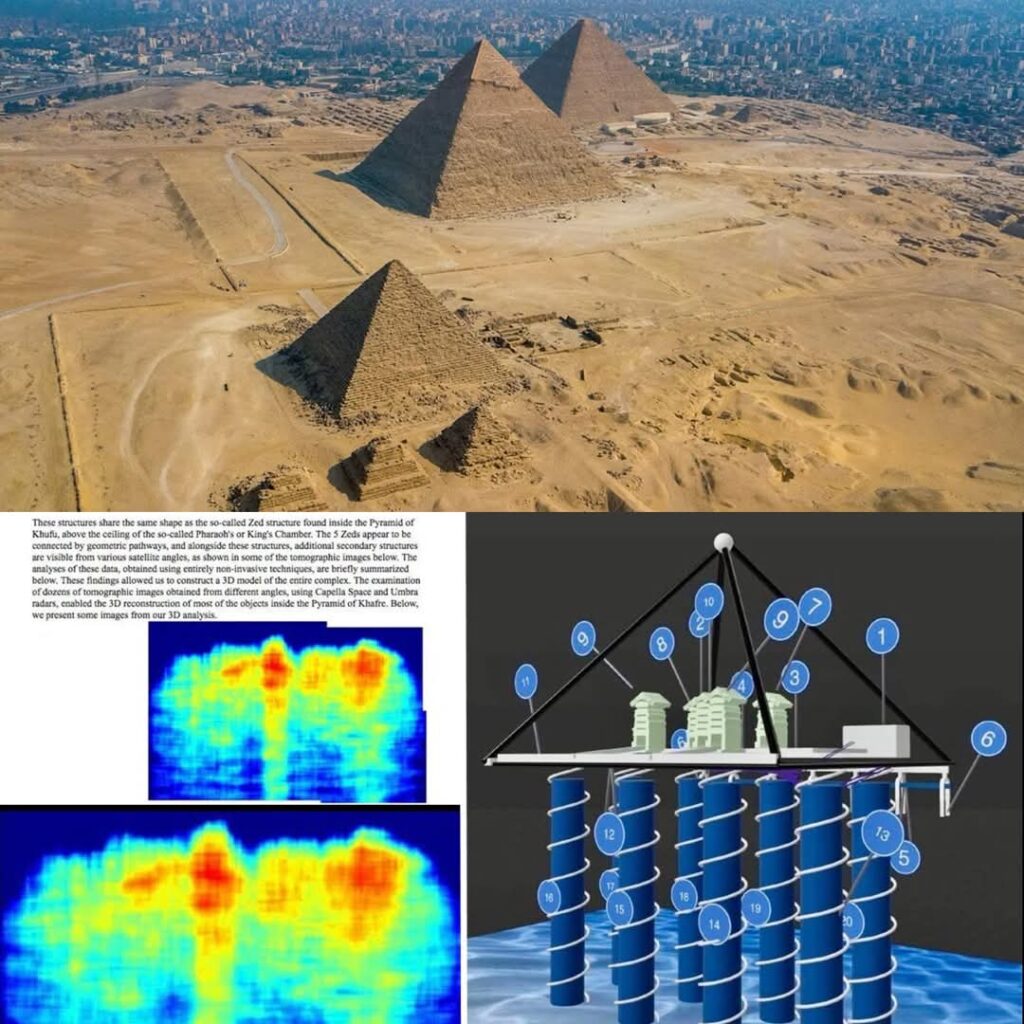

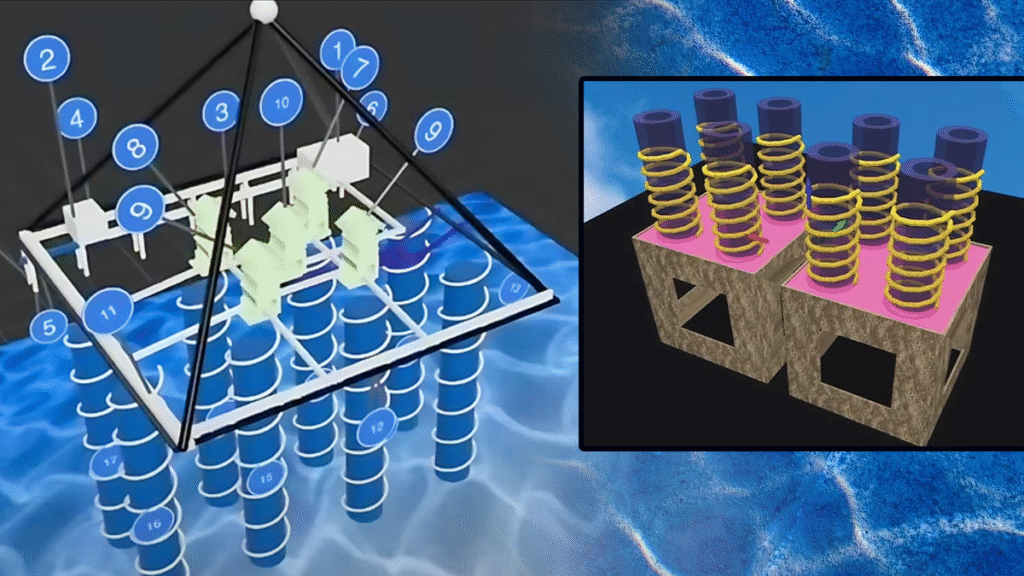

When news broke in March 2025 that Corrado Malanga former professor of the University of Pisa and Filippo Biondi of Strathclyde had used satellite P-band synthetic-aperture radar to map eight vertical cylinders, each fifteen metres across and six-hundred-plus metres deep, converging on a grid of five orthogonal chambers beneath the Pyramid of Khafre, the hairs on my arms rose exactly as they had in that mahogany reading room. Mainstream Egyptologists cried impossibility, pointing out that radar normally dies after forty metres in Giza’s micritic limestone, yet Malanga’s release included raw interferograms and phase-shift inversions awaiting replication. Even the cautious voices conceded that, if validated by forthcoming muon-flux tomography, the images would represent the largest subterranean voids ever detected on the plateau.

The Malanga dataset also revived an older thread of speculation. In trance-hypnosis sessions dating to 1933, the American medical clairvoyant Edgar Cayce spoke of a sealed “Hall of Records” to be found “between the paws of the Sphinx” when a new cycle of consciousness dawned—readings that placed a vast archive somewhere below the bedrock and tantalised generations of fringe researchers. Cayce’s timeline may have slipped, but his geographic coordinates overlap uncannily with the northernmost of Malanga’s shafts. Even scholars who reject psychic sourcing acknowledge that the Hall-of-Records myth has proven stubbornly prescient in its fixation on deep antechambers, far beneath the finished Subterranean Chamber mapped by Petrie.

What electrified me, however, was a smaller corroboration hiding in the fine print of Malanga’s report. One shaft, he noted, deviated a mere 0.15 degrees east of true north—precisely the offset my father had inked into an otherwise anonymous service-duct on his 1960s encyclopedia plates. He had believed the skew indicated a secondary vent abandoned by the dynastic remodelers; Malanga interprets it as an optical alignment compensating for atmospheric refraction at high incidence angles. Either way, a line drawn from that skew passes directly through the unfinished Subterranean Chamber and down into the newly imaged grid—an invisible architecture my father somehow intuited from surface measurements alone.

Scepticism remains essential. Muon detectors scheduled for deployment around Khafre in late 2025 will furnish density maps at depths radar cannot confidently resolve, and Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities has yet to issue any drilling permits. Still, the pattern is difficult to ignore: my father’s draftsman’s instinct, Cayce’s trance-borne coordinates, Dr A.’s classified seismograms, and Malanga’s shafts each cast a thread across decades, intersecting in the limestone beneath Giza. Followed separately, every strand frays on contact with orthodoxy; woven together, they outline a narrative in which an unknown culture—perhaps extrasolar—established beacon pyramids and entombed time-capsule vaults long before recorded history, leaving the dynastic Egyptians to inherit and embellish what they found.

I still keep the original ink overlays, their onionskin browned at the folds. On quiet nights I slide one across my desk, align it with the latest radar map on my screen, and imagine the shafts descending past strata laid down in ages when the Nile ran a different course and Homo sapiens was still a newcomer to the planet. If the muon arrays confirm Malanga’s cylinders—if a drill-core someday pulls up an alloy unknown to Bronze Age smelters—my father’s careful lines will become an unintended Rosetta Stone between epochs and, perhaps, between worlds.