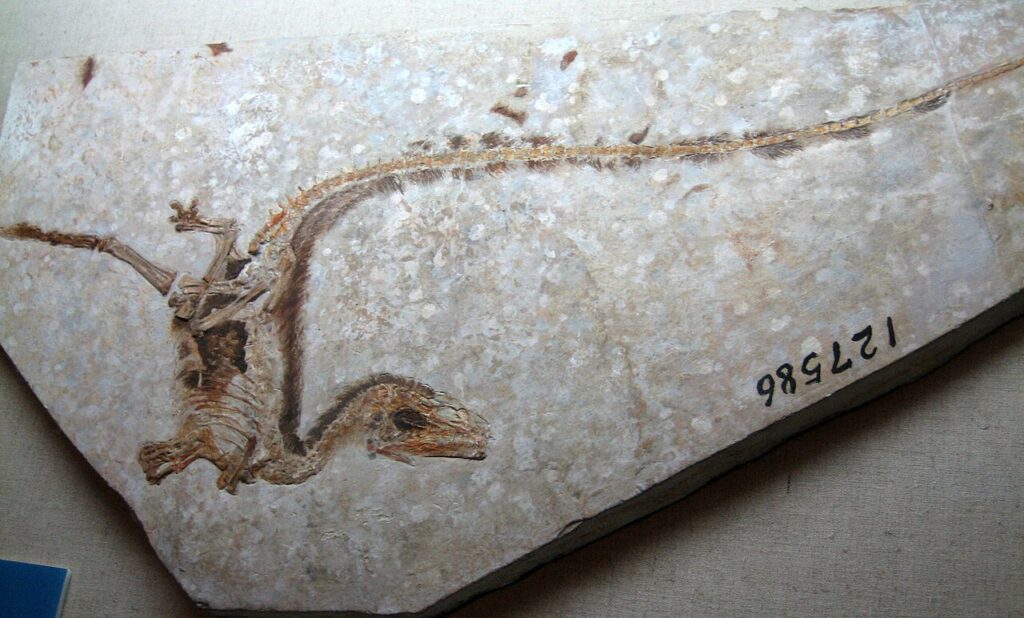

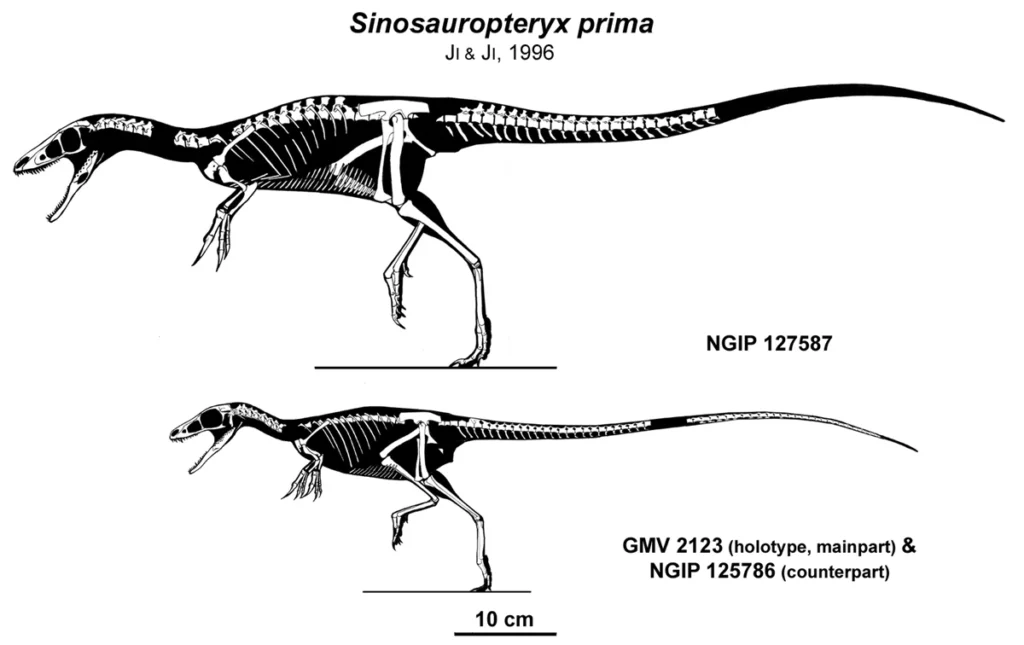

Walking through a quiet gallery in Beijing, I found myself drawn to a slab of stone that looked deceptively ordinary until the light caught the faint, dark fringed outline of a tail. Ghostly stripes shimmered under the glass. It was as if something small and quick had flickered there only a moment before. That slab belonged to Sinosauropteryx, the little predator that transformed our understanding of dinosaurs, feathers, and the deep past.

A Personal Moment in Beijing

It was the autumn of 2010. I was in Beijing between during a trip to Shanghai, wandering through the Geological Museum of China with an hour to spare. The paleontology hall was dim, the kind of quiet that makes you feel watched by extinct things. I approached the Sinosauropteryx slab without knowing what it was. Only when I leaned closer did I see the filaments around the body, hairlike structures fossilized in fine ash, and the faint bands along the tail. A small animal, preserved in a moment of stillness.

What struck me most was the intimacy of it. This was not a towering skeleton. It was the fragile outline of something that once breathed and hunted, a creature the size of a house cat.

The Origin Story on a Hillside

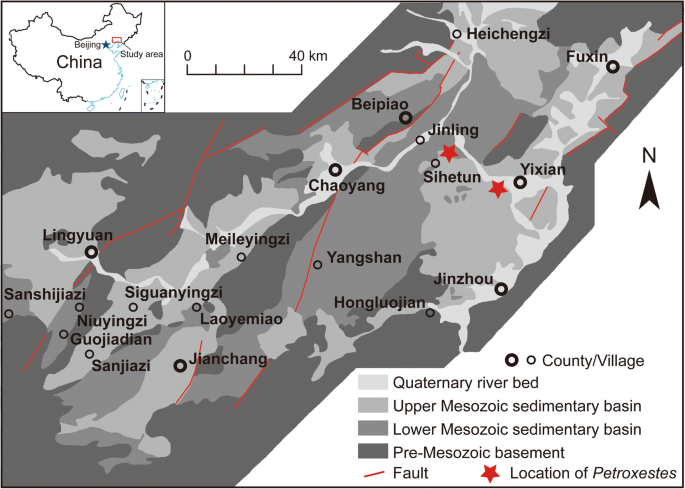

In the mid 1990s, far from any museum, a farmer in Sihetun stumbled on the two halves of that very creature. Two mirror images preserved in stone, split perfectly along a seam of ancient lakebed. In the chaotic fossil trade that soon engulfed the region, he sold each half to a different museum without realizing the scientific storm he had unleashed. That discovery ignited a fossil rush across Liaoning Province. What began with Sinosauropteryx has now yielded more than forty dinosaur species, and two entire fossil worlds that paleontologists still struggle to fully comprehend.

A guide once pointed out to me the quiet hills a short walk from Sihetun, where a 1400 kilogram feathered predator called Yutyrannus turned up. Imagine something shaped like a tyrannosaur but draped in shimmering plumage, almost ceremonial in appearance. Nearby roamed Anchiornis huxleyi, a chicken sized creature whose feathers were preserved so completely that scientists later reconstructed its colors feather by feather. One paleontologist called it the birth of color television.

The Ancient Worlds Beneath the Fields

What lies under the farms of Liaoning is larger than any single fossil. Decades of digging have revealed two exquisitely preserved ecosystems frozen in time. The Yanliao Biota, from the Jurassic period. And the Jehol Biota, from the early Cretaceous, the world Sinosauropteryx walked through. These environments were lake country surrounded by temperate forests, but also volatile lands shaken by frequent volcanic eruptions. Fine ash settled in the water, smothering animals so quickly and so gently that even feathers, skin tissue, and stomach contents survived.

From these layers emerged turtles, amphibians, fishes, mammals, pterosaurs, dozens of ancient birds, and dinosaurs of every size. The fossils look almost painted. Their stone backgrounds form soft gradients of ochre and beige, like old ink wash scrolls. Against this backdrop the skeletons leap forward with bold clarity, as if brushed in black calligraphy. A friend once told me that a Liaoning bird fossil looks like someone’s chicken dinner. It actually does.

Many of these slabs ended up in Beijing or in vast regional museums. Others passed through private hands, traded in dark apartments where priceless fossils sit beside vitamin bottles and children’s bicycles. Some slabs reveal astonishing meals preserved inside dinosaurs. A Microraptor found with the remains of a bird in its gut. A bulldog sized mammal called Repenomamus discovered with a juvenile dinosaur inside its stomach.

A Fossil Divided and a World Reconstructed

Thinking back to that moment in the Beijing museum, I remember feeling haunted by the split nature of Sinosauropteryx. The original fossil was literally torn apart, each half sent on its own path. It felt symbolic of the region itself: rich in secrets, fractured by human hands, still revealing hidden truths. In Liaoning, beauty and deception coexist. Some farmers excavate masterpieces without knowing their scientific value. Others take chisels to broken fossils, inserting a fabricated wishbone or carving a groove to fuse incompatible slabs together. Under ultraviolet light, truth and forgery glow differently.

Yet the authentic finds are astonishing. In the basement of research institutes, preparators bend over microscopes, scraping matrix from wing bones grain by grain to free details untouched since the early Cretaceous. A light tap of an air tool. A whisper of dust. A wing or feather emerges. It feels almost ceremonial, like waking something gently from sleep.

Why It Matters

For paleontologists, the Liaoning fossils illuminate the moment when birds separated from their dinosaur ancestors and took to the air. The evolutionary transitions that were once missing chapters are now visible in fine detail: hollow bones, modified lungs, complex feathers, shifting diets. For visitors, these fossils offer something simpler. They connect us to a world that feels strangely close, as if every slab is a window opening directly into a vanished forest.

Final Thoughts

When I think back to the dim hall in Beijing, I remember the quiet presence of Sinosauropteryx, curled on its slab, the faint trace of feathers still clinging to its outline. That moment felt like a whisper from deep time. A small creature running through Early Cretaceous underbrush. A lake. A sudden fall of ash. And then, millions of years later, a human leaning over glass, feeling something stir inside that cannot be easily named.

In that stillness, the past speaks in a voice as soft as dust.